Astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore, who went to space aboard Boeing's CST-100 Starliner capsule, will remain on the International Space Station and will not return until February 2025, in a SpaceX capsule that will go to space in September of this year with just two crew members, as part of the Crew-9 mission.

“NASA has decided that Butch and Sonny will return with Crew 9.” Thus, the director of the American space agency, Bill Nelson, frankly opened the press conference, Saturday (24), announcing the decision.

Nelson noted the importance of focusing on safety, and recalled the Challenger (1986) and Columbia (2003) space shuttle accidents to highlight the change in internal culture that resulted from these tragedies, which encouraged teams to express their concerns about safety when making decisions.

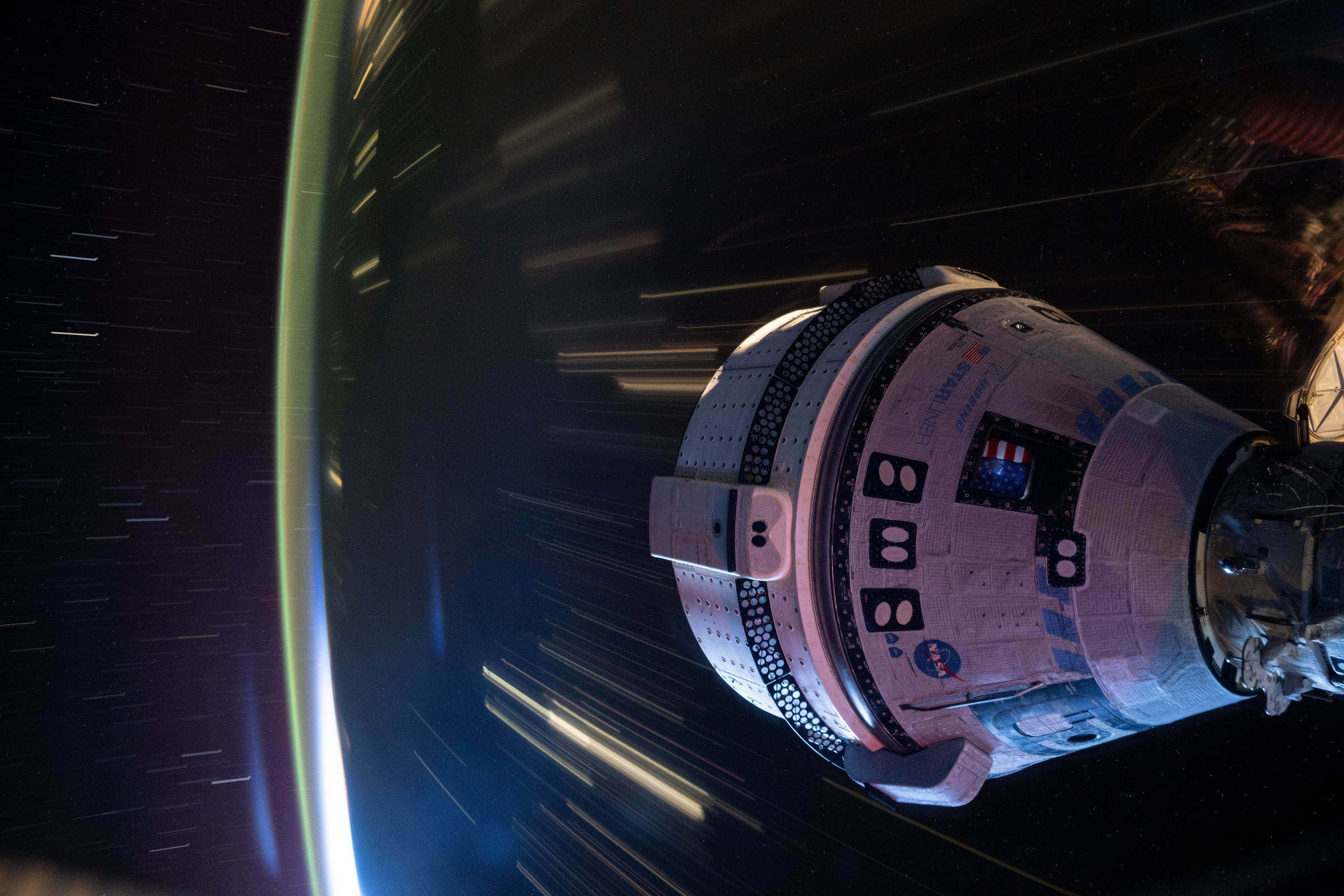

Wilmore and Williams departed for the International Space Station on June 5, on what was supposed to be a roughly eight-day mission to certify Boeing’s capsule to regularly carry crews into orbit. With the launch, they became only the second company in the world to launch astronauts into orbit, after SpaceX. Uniquely, they also became the first company to launch humans into orbit and fail to return them to Earth, which isn’t good news.

The capsule's flight was marked by problems, such as a helium leak from the service module's propulsion system, which was discovered before liftoff, but deemed irrelevant to the mission.

During the approach and docking with the ISS the next day, things got even more dangerous — the failure of five of the service module’s 28 thrusters made the procedure difficult. It’s a problem that also affected the unmanned Starliner flight in 2022.

The astronauts' stay was extended while Boeing and NASA conducted ground and orbital tests to try to understand exactly what caused the failures and ensure that nothing could threaten the astronauts' safe return. After heated discussions, the company and the space agency came to different conclusions.

For Boeing, Starliner was ready to return astronauts. For NASA, there were still uncertainties and unacceptable risks to human flight—and here the situation intersects with the history of the Challenger and Columbia accidents, which killed seven astronauts. During the shuttles, NASA learned to live with the inherent risks of those spacecraft, and the results were disastrous. This time, with lessons learned, the choice was to chart a different course.

More importantly, this time there was already a safer alternative ready to go: using SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule, which is operational and has carried out 13 successful manned flights, and the next flight is scheduled for Monday (26). On the special Polaris Dawn mission.

The space station, which has missions that last about six months, had to be reprogrammed. With Wilmore and Williams still in space, they are now part of a team that will conduct experiments and maintenance on the orbiting complex until February next year. They will be joined by two astronauts on SpaceX’s Crew-9 mission in September, and all four will return in the same capsule at the end of the mission, in February 2025.

Starliner future

With this decision, Starliner will be returned to Earth without a crew in September, bringing a sad end to its mission.

Regardless, a successful return would be valuable in helping to certify the capsule for future regular flights. It’s unclear whether that would be enough to make the next crewed flight possible, or whether Boeing would have to demonstrate its capsule on a new unmanned flight before trying again.

It's also not clear whether Boeing wants to continue with the project. The capsule's development has already cost the company $1.6 billion in losses. Recent events certainly don't help reduce future losses.

The contract with NASA for crew transport, signed in 2014, at a fixed cost, closed at US$4.2 billion (R$23.2 billion), for the development of the vehicle and one unmanned flight and one manned flight. At this point, Boeing had already had to make two unmanned flights, and the first manned flight ended up incomplete.

Asked how confident he was that Boeing would continue working on Starliner to support the agency’s commercial initiative, Bill Nelson replied, “100 percent.” For NASA, this is very important because the program wants redundancy: two different providers for the same service, so one is up and running while the other may have problems.

It is precisely this iteration that has allowed NASA this time to choose to return astronauts to Crew Dragon, rather than risk returning to Starliner. SpaceX has also developed its capsule for a fixed-price contract ($2.6 billion, about R$14.4 billion) and has been flying regularly to the ISS with its crew since 2020.

“Wannabe internet buff. Future teen idol. Hardcore zombie guru. Gamer. Avid creator. Entrepreneur. Bacon ninja.”