Science has a lot of magic (ironic, right?)

Scientists say they have finally found the remains of Theia, an ancient planet that collided with Earth to form the Moon

for every Jackie WattlesCNN

Subscribe to the scientific newsletter The theory of wonders From CNN. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs, and more

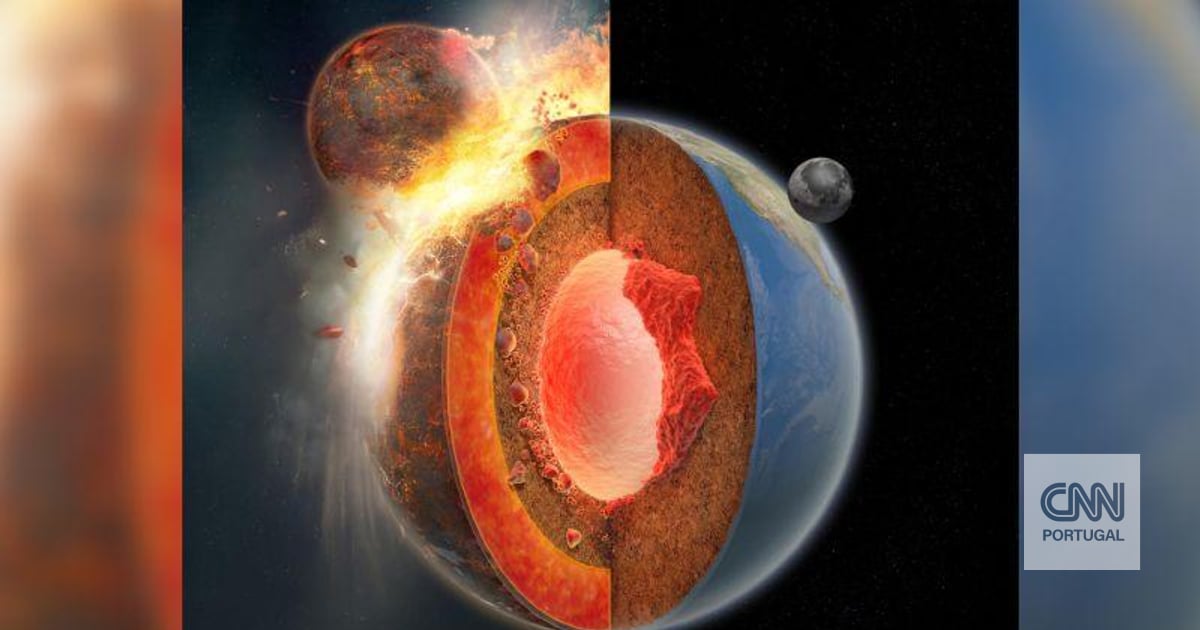

Scientists agree that an ancient planet collided with Earth as it was forming billions of years ago, dumping debris that collected into the moon that now decorates our night sky.

The theory, called the “giant impact hypothesis,” explains many basic features of the Moon and Earth.

But a glaring mystery remained at the heart of this hypothesis: What happened to Thea? Direct evidence of its existence has remained elusive. No parts of the planet have been found in the solar system. Many scientists assumed that all the debris that Theia left on Earth was mixed in the fiery cauldron located in the interior of our planet.

However, a new theory suggests that the remains of the ancient planet are still partially intact, buried beneath our feet.

Theia’s molten slabs may have been embedded in Earth’s mantle after the impact, before solidifying, leaving bits of the ancient planet’s material lodged in Earth’s core, about 2,900 kilometers below the surface, according to a study published in the journal Nature.

A new and bold idea

If the theory is correct, it will not only provide additional details to complement the giant impact hypothesis, but will also answer a lingering question for geophysicists.

Geophysicists already knew that there were two huge, distinct bubbles embedded deep within the Earth. The blocks – called “Large Low Velocity Provinces” or LLVP (abbreviation in English) – were first discovered in the 1980s, with one found under Africa and the other under the Pacific Ocean.

These bubbles are thousands of kilometers across, and are likely denser in iron than the surrounding mantle, making them prominent when measured by seismic waves. But the origin of the bubbles, each of which is larger than the moon, remains a mystery to scientists.

But for Qian Yuan, a geophysicist and postdoctoral fellow at Caltech and lead author of the new study, the way he views LLVP changed forever when he attended a symposium in 2019 at Arizona State University, his alma mater. At this point he learned new details about Theia, the mysterious projectile that supposedly struck Earth billions of years ago.

As a geophysicist by training, he was aware of the mysterious bubbles hidden in the Earth’s mantle.

Yuan had a eureka moment, he says.

He immediately began consulting scientific studies, looking to see if anyone else had suggested that the LLVP could be parts of Theia. But no one did.

Yuan says he only talked about his theory to his advisor.

“I was afraid to talk to other people because I was afraid they would think I was too crazy.”

Interdisciplinary research

Yuan first proposed his idea in a paper he submitted in 2021, but it was rejected three times. Reviewers said there were not enough models for the giant effect.

It was then that he met scientists who conducted exactly the kind of research Yuan needed.

Their work, which assigned Theia a certain size and impact velocity in modeling, suggests that the ancient planet’s collision may not have completely melted Earth’s mantle, allowing Theia’s remnants to cool and form solid structures rather than mixing into Earth’s inner soup.

“The Earth’s mantle is rocky, but it’s not like solid rock,” says Steve Desch, study co-author and professor of astrophysics at Arizona State’s College of Earth and Space Exploration. “It’s this high-pressure magma that’s a little viscous and has the consistency of peanut butter — and it’s basically sitting on a very hot stove.”

In that environment, if the material that makes up the LLVP was too dense, it wouldn’t be able to clump together in the irregular configurations in which it appears, Desch says. If its density is low enough, it will simply mix with the turbulent mantle.

The question was: What is the density of the matter left behind by Theia? Can it match the density of LLVP?

(Desch wrote his own paper in 2019 in which he sought to describe the density of matter that Theia could have left behind.)

Yuan says the researchers sought to create high-resolution models with 100 to 1,000 times greater accuracy than their previous attempts. And the calculations agreed: If Theia had a certain size and consistency and hit Earth at a certain speed, the models showed that it could, in fact, leave behind huge chunks of its interior in Earth’s mantle and also generate the debris that would create our Moon.

“That was really exciting,” Yuan says. “I’ve never done that before.”

Building a theory

The study Yuan published this week includes co-authors from multiple disciplines at multiple institutions, including Arizona State, the California Institute of Technology, the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, and NASA’s Ames Research Center.

When asked whether he expected to encounter resistance or controversy over such a new concept — that slabs of material from an ancient extraterrestrial planet are hidden deep within the Earth — Yuan replied: “I also want to stress that this is an idea, a hypothesis.” “There is no way To prove that this is the case. “And I call on others to do this – this investigation.”

“This work is compelling and makes a very strong case,” Desch adds. It even seems “a bit obvious in retrospect.”

However, Seth Jacobson, assistant professor of planetary sciences at Michigan State University, admits that the theory may not be accepted anytime soon.

“LLVPs are in themselves a very active area of research,” says Jacobson, who was not involved in the study. The tools used to study them are constantly evolving.

He adds that the idea of Thea creating the LLVP is undoubtedly an exciting and attractive hypothesis, but it is not the only one out there.

Another theory, for example, posits that LLVPs are actually piles of oceanic crust that have sunk deep into the mantle over billions of years.

“I doubt that defenders of other hypotheses about LLVP formation will abandon them just because this one appears,” Jacobson adds. “I think we will continue to discuss this matter for some time.”

“Coffee trailblazer. Social media ninja. Unapologetic web guru. Friendly music fan. Alcohol fanatic.”

More Stories

Does TikTok know you better than your mom or friends? Social Networking Algorithm Leaves Users in Uproar – Executive Summary

Google Pixel 8a: official images confirm more details about the smartphone

Leak Points: Windows 11 24H2 will have a watermark on PCs without AI support